Dalí & Duchamp: ‘A Matter of the Artist’ (2017) – Art Review

Introduction

Inside a majestic square, much like a castle, we found ourselves approaching the ticket office of what seems like a largely classical affair. It was here to be the host of some of the most daring artists of the 20th Century. Ironically, artists who were keen to point a rear end to the established classy values of the bourgeoisie. Salvador Dalí, was a Surrealist artist and provocateur of the mainstream masses and possibly the most famous amongst the Surrealist artists. Whilst Marcel Duchamp is to blame for what we can now call modern art or more accurately conceptual art. Where Dalí is likely well known as ‘the melting clocks guy’, Duchamp has a relative obscurity, but infamously exhibited an upturned urinal in an ‘anything goes’ exhibit and got it disqualified. (The Persistence of Memory, 1934 and The Fountain, 1917 respectively.) Here, their works are exhibited together in the same space and side by side. The parallels between Dada and Surrealism are immediately apparent and, despite not being exclusive to the movements, Duchamp and Dalí are known for their contributions to the respective art/anti-art movements.

The Artist as Personal

Walking into the first room, we have a depiction of origins. Seeing some of Dalí’s early work and some of Duchamp’s we can see some explorations of Cubism that perhaps isn’t too widely known. We also have, for side by side comparisons, a portrait of their father done by each artist. Continuing the personal feel, we’re able to see a rather intimate touch to the artist’s life’s in pictures and postcards as well as notes about their work. For example, Marcel Duchamp’s destruction of the artist continued to many different pseudonyms used for his work including R. Mutt and Rrose Sélavy. Rrose Sélavy, perhaps being the most used alias of the artist, here elaborated by a note that possibly wasn’t ever meant to be seen. This note explained the reasons and thoughts of Marcel Duchamp for choosing Rrose Sélavy, whilst a few examples of this alias are included; amongst them are photos of Marcel Duchamp dressed as Rrose Selavy by Man Ray. Rrose Sélavy is one of Marcel Duchamp’s famous puns, doubling as ‘Eros C’est la Vie’ (Love, such is life). Another included in the exhibit is Marcel Duchamp’s affront to the Mona Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q, which also puns: ‘She has a hot arse’ in French (‘Elle a chaud au cul’).

The Unpainted Art

Moving through the rooms we see some more famous works including replications of Fountain and Bicycle Wheel. The rather large cabinet case containing them dwarfing and surrounding the Dalí made Lobster Telephone, but Dalí’s contributions to ‘readymades’ (Duchamp’s name for the found objects he puts into exhibitions) or even sculpture or objects, weren’t as numerous as Duchamp’s. However, looking around the room there were beginning to show signs of the sheer lack of Dalí’s presence. With a few paintings here and there but a lot more to show for Duchamp. Boasting works like Étant donnés and Portrait of Chess Players – continuing on to the next room. Here, in the third room of the exhibit, the strenuous connection between the artists feels all the more strained. Interesting to include two projections side by side by some of their contributions to cinema. However, they remain to be strange choices and imply deeper connections than were there. Side by side, Anémic Cinema and a clip from Spellbound, despite the connections they have in cinema, couldn’t be further apart. Anémic Cinema (1926), a personal avant garde film comprised of visual puns on a spinning board. Whilst the sequence from Spellbound (1945) is a restricted artist’s output into a commercial film, with characters and objects running through a dream-like story. Marcel Duchamp’s film with Maya Deren, Witch’s Cradle (1944), would have perhaps made a better fit – despite its incomplete nature.

Chess a Hidden Art

From here we delve into the world of Chess and Dalí’s gift to Duchamp in Chess Pieces, Homage to Marcel Duchamp. Dalí and Duchamp were certainly friends, their connection to each other is evident by their postcards and photos together in casual settings, that were well established in the first room. Here we see the personal continue; Chess, Marcel Duchamp’s love, being at the forefront, whilst Dalí only tributes him. It is no secret their appreciation of Chess, also evident in many works by Duchamp attesting to the movements and calculations of Chess – even demonstrated by a TV interview with Duchamp, where he talks about Chess. Other TV mentions of Dalí are included, including elaborate Dinner’s and Bullfighting events but, much like the short films, there doesn’t seem to be much of a connection, and a gain the focus is with Duchamp and Chess.

Conclusion

The exhibit feels like a Curators need to combine the two artists. They were certainly friends and shared similar time periods, though Duchamp (b. 1887) was a generation before Dalí (b. 1907). They both enjoyed elements of reinventing the artist and their persona. Dalí the grand Surrealist and Duchamp, with the destructive (or at least disassociating) alter egos. Their looks to other mediums: cinema and objects, is also evident. However, the connection feels forced and the Curator clearly is more interested in Duchamp than Dalí; they include some famous works by both: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (reconstructed) and Apparition of a Face and Fish Bowel on a Beach; but for the most part keep the exhibit to a personal edge and favouring the works of Marcel Duchamp. This could have been a budgetary restriction but it looks more like a love of Ducahmp, a look at his life and how he was with the artist’s around him, with a primary focus on Dalí – though there are a few other artists present: Man Ray and Richard Hamilton (who reconstructed The Bride Stripped Bare y her Bachelors, Even). It is, however, a touching look at a personal side to a man, Marcel Duchamp, who liked to be kept hidden.

Dalí / Duchamp will run until the 3rd of January 2018 at the Royal Academy of Arts.

Further Reading

Dalí / Duchamp at the Royal Academy of Arts

Art History’s Odd Couple – A Review

If you liked this…

Dalí Museum, Figueres – Art Review

Man Ray, Exhibition at National Portrait Gallery – Art Review

Dorothea Tanning – Web Dreams 2014 – Art Review

Francesca Woodman – Zig Zag 2014 – Art Review

Tristan Tzara. Dada: ‘Handkerchief of Clouds’ & ‘Gas Heart’ (2016)- Theatre Review

See a selected list of works below:

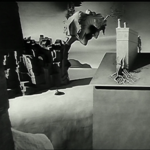

- Still from Spellbound, Hitchcock / Dalí, 1945

- Fountain, Duchamp, 1917

- Bottle Rack, Duchamp, 1914

- Adam and Eve, Man Ray (Duchamp as subject), 1924/5

- Portrait of Rrose Sélavy, Man Ray (Duchamp as Subject), 1921

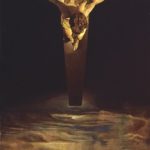

- Christ of Saint John of the Cross, Dalí, 1951

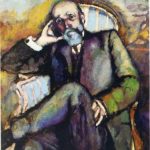

- Portrait of the Artist’s Father, Duchamp, 1910

- The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, Duchamp, 1923

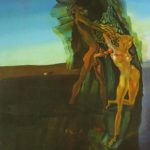

- A Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds, Dalí, 1936

- Bicycle Wheels, Duchamp, 1913

- Prelude to a Broken Arm, Duchamp, 1915

- Why Not Sneeze, Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp, 1921

- Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (Eve Babitz), Julian Wasser, 1963

- L.H.O.O.Q., Duchamp, 1919

- Female Fig Leaf, Duchamp, 1961

- Étant donnés, Duchamp, 1946-1966

- Dalí and Duchamp, Unknown

- Lobster Telephone, Dalí, 1936

- Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach, Dalí, 1938

- Painting Holiday, Unknown, 1958

- William Tell and Gradiva, Dalí, 1931

- Dust Breeding, Duchamp/Man Ray, 1920

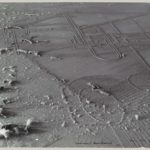

- Still from Anémic Cinema, Duchamp,

- Portrait of My Father, Dalí, 1925

Leave a Reply