Kaiju Cinema Narratives – An Essay on Film

Kaiju Cinema Narratives

Introduction

This is a short essay to explore the typical narrative structures that define a phenomenon in film history – Kaiju cinema. In looking at films like Gojira / Godzilla (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1954), Daikaiju Gamera / The Giant Monster Gamera (d. Noriaki Yuasa Japan 1965), Mosura / Mothra (d. Honda Japan 1961), Godzilla (d. Gareth Edwards USA 2014), King Kong (d. Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Shoedsack USA 1933), Jurassic Park (d. Steven Spielberg USA 1993), Jurassic World (d. Colin Trevorrow USA/China 2015), The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (d. Eugène Lourié USA 1953), Pacific Rim (d. Guillermo del Toro USA 2013), Godzilla (d. Roland Emmerich USA/Japan 1998), I hope to position some of the fundamental aspects of what makes a Kaiju film a Kaiju film. A lot of my research is indebted to David Kalat’s book: A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series (A. Kalat, David. A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series McFarland & Co, 2010, (2nd Edition)), which gives a lot of the films mentioned a proper analysis.

A brief history

So what are Kaiju films? Kaiju, is Japanese and means big monster. This term which means ‘Strange Monster’[1] but is used to categoriseJapanese giant monster movies (also see Daikaiju[2]). This reflected a big phenomenon in the 1950s in Japanese cinema that may have begun with Gojira. However, this film wasn’t the first in giant monsters being on the screen. King Kong (1933) is probably one of the most famous examples of a movie featuring a giant animal. King Kong was a huge success[3] (also see rottentomatoes.com critics score of 98% and audience score of 86%[4]) but the next famous examples of films featuring giant animals or dinosaurs only arose again in the 1950s. Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is an example of the many sci-fi films or horror films to come out in the ’50s.[5] These films were typical b-movies for the most part but would appear to be of their own phenomenon but included genres like a development of monster movies (more on genre later). The American made films were very different from the films that came out in Japan of this time (or slightly later), namely, Gojira, Sora no daikaiju Radon / Rodan (d. Honda Japan 1956), Mosura and Gamera.

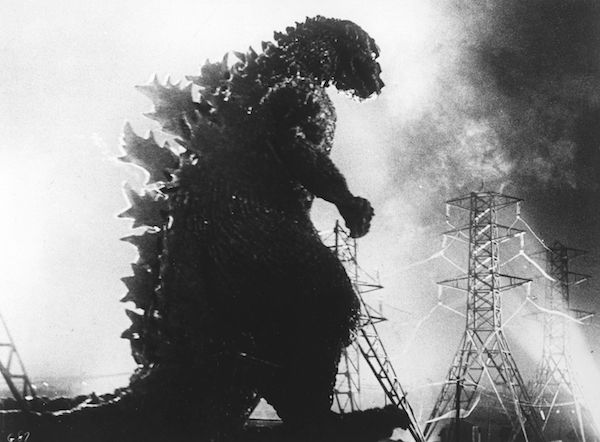

Gojira is a famous example of an anti-nuclear weapons film.[6] Gojira, the monster, representing the destructive power of both the nuclear attack of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the second world war, as well as the anger of nature. Allowing Japan to “see their nation as both victim and savior”[7] in Gojira is significant. Mosura was a similar film in many respects but Mosura’s origin story helps Mosura to be more representational of a higher morality. “In every way, Mothra appears morally and spiritually superior [to man]”[8] She sides with the earth sometimes against and sometimes with mankind. Gojira continued a successful series of films that continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s and included other world issues. Gojira tai Hedora / Godzilla vs. Hedorah (d. Yoshimitsu Banno Japan 1971) was about pollution[9] and Invasion of the Astro-Monster (d. Honda Japan/USA 1965) and Ghidorah, The Three Headed Monster (d. Honda Japan 1964) reflected a growing preoccupation with sci-fi, space and aliens.[10] Gamera followed a similar route thematically in some respects but reveled in being a children’s hero.[11] The Heisei era films like Gamera Daikaiju Kuchu Kessen / Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (d. Shusuke Kaneko Japan 1995) and Gojira tai kingu Ghidora / Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (d. Kazuki Omori Japan 1992) continued the nuclear power image and made it darker and more horrifying, thus taking these films back to Gojira as a horror.[12] In the last 20 years several American films have attempted to capitalise on this phenomenon like Godzilla (1998), that was a critical failure(rottentomatoes.com critics score of 16%[13], metacritic.com gives a score of 32[14] and the writer even apologised for the film[15]), and more recently films like Pacific Rim and Godzilla (2014), their reaction being a bit more mixed (Pacific Rim’s rottentomatoes.com critics score of 71%[16] and Metascore of 64[17], whilst Godzilla (2014) is 74%[18] and 62[19]) but why? Meanwhile films like Jurassic Park and Jurassic World represent very different movements in film but none-the-less very important ones as we shall see later.

American & Japanese Monster Movies

USA

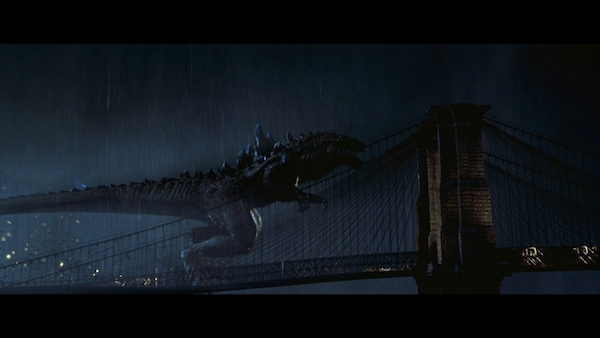

So what do King Kong, Beast From 20,000 Fathoms and Godzilla (1998) all have in common? King Kong is about Americans going to a foreign country, capturing a large beast that they take back to America and then runs amok in America. This is a simplified version of the story but these are the points I wish to focus upon. Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is about Americans waking up a dinosaur that then runs amok in America. Again simplified but are you starting to see a pattern? Godzilla (1998) is about a French (though still western) nuclear test creating a giant monster that runs amok in America. See a pattern? If we focus on the 1950s once again it is clear that there is a big fear about nuclear power and there is a lot of criticism. “America had to deal with the mass trauma over using a nuclear weapon on another nation, and also the perpetual fear of future apocalypse.”[20] This is a power that could be very dangerous if exploited in the wrong way. Beast from 20,000 Fathoms again has a monster representing nuclear power and how it can either rouse nature or create its own destruction. If you look at It Came From Beneath the Sea (d. Robert Gordon USA 1955), Them! (d. Gordon Douglas USA 1954) and Attack of the 50ft Woman (d. Nathan Juran USA 1958) we just see more examples of this kind of idea. “These movies particularly manifest society’s mistrust of the intellectual, in the form of the mad scientist, who must often have his destructive creations negated by “ordinary” citizens.”[21] America acts in a way that causes widespread destruction either by awakening nature or as created by and being a symbol of nuclear power.

Japan

Now, Gojira depicts a similar thing but with one very important difference: Japan is the victim. In Beast From 20,000 Fathoms and all these other films the monster comes, runs amok and America is attacked but then hunts down the beast. America was never in any real danger, just mild annoyance. King Kong works under a similar premise but without the nuclear power theme. King Kong isn’t a major threat. In Gojira the monster destroys and shatters Tokyo but importantly stays and even in Mosura and Gamera there is this sense that the monster has taken over. This may seem like a small difference but it’s important. Godzilla (1998) wasn’t a successful film for many reasons[22] but one major flaw is that the monster didn’t pose any real threat to America. The monster was also very different in design from the monster in Gojira removing key aspects like his breath weapon but the key thing is that it wasn’t a threat.

In the 1950s

If we take the narratives of Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, Godzilla (1998) and Gojira (1954); and compare them, we can see that Beast From 20,000 Fathoms and Godzilla (1998) are more similar than Gojira (1954) and Godzilla (1998)[23]. Godzilla (1998) is of a monster being created by an atom bomb test and the creature runs amok in New York as the army chases it away. Gojira, however, has an atomic bomb awaken a seemingly unstoppable monster. Considering that one is meant to be a remake we can see one of the huge problems here. This also represents the huge difference in tone from what I would call ‘Monster-on-the-Run’ films and Kaiju films. ‘Monster-on-the-Run’ films that were big in America in the 1950s represent films where the monster is never a huge threat and America is always on top of it. Kaiju films represent nature or nuclear power as a huge threat to humanity and therefore humanity are depicted as struggling victims.

Contemporary

So what about Godzila (2014) and Pacific Rim (2013)? As film theory on kaiju films grew[24] there was a better understanding of these films. This is clear to see in both films. Godzilla (2014) shows Godzilla as a significant force and un-defeat-able once again. This film represents a return to the films that gave the continued success of kaiju films. Very few Gojira films and Gamera films do not feature two giant monsters fighting. The power is not with humanity it is only with another monster. In Mosura tai Gojira (d. Honda Japan 1964) Mosura, representing that higher spiritual superiority defending the earth, arises to battle the threat of nuclear power in Gojira. In fact David Kalat elaborates on this idea stating:

“The Notion of Toho’s Kaiju as monster-gods recurs in many of the films. (…) the concept distinguishes Toho’s output from American films. These giant monster-gods are also like super-weapons, called into action when competing interest groups cannot solve their differences peacefully. (…) Only when the humans peaceably resolve their problems do the monsters go away – another departure from the American pattern, in which military action nearly always triumphs over monsters”[25]

A common theme throughout the Gojira/Godzilla series, that the problems have to be solved by the kaiju. Man is powerless and lacks the moral superiority of Mosura/Mothra for example to resolve the issues at hand. Godzilla (2014)’s very tagline ‘let them fight’ capitalises on this idea. A Kaiju film needs the power of a giant monster to destroy cities and to pose that all important threat that can’t be defeated by mankind. This is their power and Godzilla (1998) does not get this but Godzilla (2014) does and so does Pacific Rim. However a huge problem with Pacific Rim J. F. Sargent that identifies in his article ‘How ‘Pacific Rim’ Got Kaiju Wrong’[26], lies in a different aspect of the narrative. Gojira, Gamera, Radon and Mosura amongst many other films were critical of the use of nuclear power. (If not a thematic consideration that’s important to Kaiju cinema then one could argue that it’s an extension of man’s power over the Kaiju.) Pacific Rim uses nuclear power to resolve the issue of the giant monsters, despite seeing humanity as victims they’re still not as powerful as man. Once again there’s a problem with the depiction of Kaiju cinema.

Concerning Jurassic Park

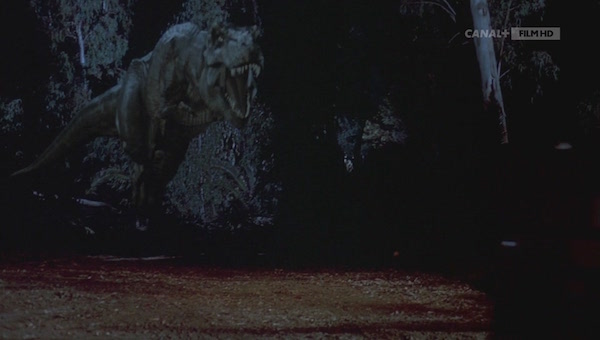

Now, Jurassic Park and Jurassic World are different in themselves. Jurassic Park being about monsters (technically dinosaurs) that were created and nature taking over the control that the scientists had. In many ways Jurassic Park is very different to all other films mentioned but it also has many similarities. Jurassic Park does depict people as victims and nature as powerful but also there is little that shows that the monsters can threaten humanity on such a global scale. They don’t knock down buildings and clear cities and they don’t attract political attention. Gojira’s nuclear power threatens countries and asks for political decisions about that power, Mosura being the power of nature again threatens countries and asks for their political decisions, King Ghidorah representing aliens (he comes from space or the future) threatens countries and asks for political decisions. The monsters in Jurassic Park are a major threat but only to the scientists and to the people involved.

Concerning Jurassic World

Funnily enough, Jurassic World has a bit more to do with Kaiju cinema. The idea of ‘let them fight’ comes up as more central to the story and in many ways the film can be seen as exactly what Godzilla (2014) was. In Godzilla the MUTOs were found and fought to no avail and the latent Godzilla eventually steps in to end the threat. In Jurassic World the I-Rex is created and when it escapes it is fought to no avail and the latent T-Rex (and Mosasaur, though more screen-time is given to the T-Rex fight) eventually steps in to end the threat (with help from the Velociraptor – Blue). Despite the huge similarities between Jurassic Park, Jurassic World and the rest of kaiju cinema, there are again some differences that help define the genre. There isn’t a global threat, even despite the common theme of ‘let them fight’, which also usually indicates man’s helplessness in the face of such a beast.

Conclusion

The unfortunate Godzilla (1998) and Pacific Rim, as well as films like Jurassic Park, Beast From 20,000 Fathoms and Godzilla (2014) all help to define differences in the genre. A Kaiju film needs to pose a political or global threat in the destruction of civilisation through a key issue like nuclear power, aliens, pollution and nature itself, all represented by a giant monster. Humanity are victims not heroes. Some of these points may sound a bit basic and/or splitting hairs but horror films require people to be victims whilst action films require people to have some key power over what they’re attacking. (This is a very simplified way to look at it but it’s a small but important aspect). They are completely different genres. This may go some way to explain the problems inherent in some of the films and why Gojira and Beast From 20,000 Fathoms are very different with different legacies. Kaiju and ‘Monster-on-the-Run’ films.

[1] History of the term ‘Kaiju’, which predates film considerably, though an extensive look at the term is translated on this site. Author Unknown, ‘Kaiju’ on pixiv.net at http://dic.pixiv.net/a/%E6%80%AA%E7%8D%A3 (last accessed using an online translator 25/03/2017) For further interest in the term also see this book: Kenichi, Nakane (a). A Study of Chinese Monster Culture: Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media. unknown date and publication but in Japanese here: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/110007480367.pdf?id=ART0009307082&type=pdf&lang=en&host=cinii&order_no=&ppv_type=0&lang_sw=&no=1490606075&cp= (last accessed 25/03/2017) This book forms the basis of a lot of online research on the term but to my knowledge there’s not an English translation and so my research tends to end here.

[2] ‘The lone Kaiju’ ‘Kaiju’ on urbandictionary.com at http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=kaiju (last accessed 25/03/2017) Daikaiju is often pared in definitions of Kaiju and although many definitions exist, I found this to be one of the most comprehensive.

[3] Author Unknown. ‘King Kong (1933)’ on the-numbers.com at http://www.the-numbers.com/movie/King-Kong-(1933)#tab=summary (last accessed 25/03/2017) Box office results far exceeded its budget.

[4] Author Unknown. ‘King Kong (1933)’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1011615_king_kong (last accessed 25/03/2017)

[5] Author Unknown, ‘The 50s B-Movie’ on glyndwr.ac.uk at https://www.glyndwr.ac.uk/rdover/other/the_50s_.htm (last accessed 25/03/2017)

[6] Suvarna, Vivek. ‘Gojira: The Japanese Original’ on thefocuspull.com at http://www.thefocuspull.com/features/gojira-japanese-original/ (last accessed 25/03/2017)

[7] Kalat, David. ‘Introduction’ in Kalat, David. A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series McFarland & Co, 2010, (2nd Edition) p5.

[8] Kalat, David. ‘Mothra vs. Godzilla’ in ibid (…) p69

[9] Gates, Anthony. ‘Godzilla vs Hedorah aka Godzilla vs the Smog Monster’ on easternkicks.com at http://www.easternkicks.com/reviews/godzilla-vs-hedorah-aka-smog-monster (last accessed 25/03/2017)

[10] Ghidorah, as well established by Invasion of the Astro-Monster, is a space alien by definition and is often controlled throughout the Godzilla series by aliens. This marks a divide between earth monsters and alien monsters as earth is defended from space. See a line from Ghidorah, The Three Headed Monster: “He’s saying all three of us should fight together against this new monster to save the Earth.” Mothra quoted by the Shobihin.(Mothra is generally regarded as female but not all subtitles will reflect this.

[11] In Daikaiju Gamera / The Giant Monster Gamera (1965) Gamera saves a child, Toshio, from a falling lighthouse. This would become a long standing theme in the Gamera films where children would have a greater and greater place in the plot. Hence Gamera has the title of ‘Friend to all Children’. This is also comparable to the light hearted tone that the showa series of Gamera films (1965-1980) take to having children as their target audience.

[12] “For the rebirth of the Godzilla legend, Toho decided to once again portray the King of the Monsters as an evil creature.” Robert Biondi, “The Evolution of Godzilla – G-Suit Variations Throughout the Monster King’s Twenty One Films”, G-FAN #16 (July/August 1995)

[13] Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/godzilla/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[14] Author Unknwon. ‘Godzilla 1998’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/godzilla-1998 (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[15] Vary, Adam B. ‘‘Godzilla’:’I know I screwed up,’ says Dean Devlin’ on ew.com at http://ew.com/article/2012/07/27/dean-devlin-on-godzilla-reboot/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[16] Author Unknown. ‘Pacific Rim (2013)’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/pacific_rim_2013/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[17] Author Unknown. ‘Pacific Rim’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/pacific-rim (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[18] Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla 2014’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/godzilla_2014/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[19] Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla 2014’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/godzilla-2014 (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[20] Wilson, Karina. ‘1950s’ on horrorfilmhistory.com at http://www.horrorfilmhistory.com/index.php?pageID=1950sa (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[21] ibid.

[22] Tone, look, animal over destructive symbol and for a lot more in depth failures look to cinemasins episode ‘Everything wrong with Godzilla in 7 minutes or less’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oF4RxoBzTpo (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[23] Den of Geek’s article seems to agree: “despite their use of the name, what they made was a reboot of the 1953 film, not the 1954 film or any of the Godzilla films that followed.” Knipfel, Jim. ‘Godzilla 1998: What went wrong with the Roland Emmerich film?’ on denofgeek.com at

http://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/godzilla/233267/godzilla-1998-what-went-wrong-with-the-roland-emmerich-film (last accessed 27/03/2017)

[24] “over the years, as the fan press gradually started to grow and cohere into a movement” Kalat, David (A). ‘Preface to the New Edition’ in Kalat, David. A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series McFarland & Co, 2010, (2nd Edition) p1

[25] Kalat, David. ‘Mothra’ in Kalat, David (a). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series. McFarland & Co, 2010, (2nd Edition) p54

[26] Sargent, J. F. ‘How ‘Pacific Rim’ Got Kaiju Wrong’ on filmschoolrejects.com at https://filmschoolrejects.com/how-pacific-rim-got-kaiju-wrong-c154c1499531 (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Bibliography

Books

Barr, Jason (a). The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema’s Biggest Monsters. McFarland & Co, 2016.

Kalat, David (a). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series. McFarland & Co, 2010, (2nd Edition)

LeMay, John (a). The Big Book of Japanese Giant Monster Movies: Volume One: 1954-1980. Createspace Independent Publishing, 2016.

Tsutsi, William M. (a). Godzilla on My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Films

Attack of the 50ft Woman (d. Nathan Juran USA 1958)

Daikaiju Gamera / The Giant Monster Gamera (d. Noriaki Yuasa Japan 1965)

Gamera Daikaiju Kuchu Kessen / Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (d. Shusuke Kaneko Japan 1995)

Ghidorah, The Three Headed Monster (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1964)

Godzilla (d. Roland Emmerich USA/Japan 1998)

Godzilla (d. Gareth Edwards USA 2014)

Gojira / Godzilla (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1954)

Gojira tai Hedora / Godzilla vs. Hedorah (d. Yoshimitsu Banno Japan 1971)

Gojira tai kingu Ghidora / Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (d. Kazuki Omori Japan 1992)

Invasion of the Astro-Monster (d. Ishiro Honda Japan/USA 1965)

It Came From Beneath the Sea (d. Robert Gordon USA 1955)

Jurassic Park (d. Steven Spielberg USA 1993)

Jurassic World (d. Colin Trevorrow USA/China 2015)

King Kong (d. Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Shoedsack USA 1933)

Mosura / Mothra (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1961)

Mosura tai Gojira (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1964)

Pacific Rim (d. Guillermo del Toro USA 2013)

Sora no daikaiju Radon / Rodan (d. Ishiro Honda Japan 1956)

The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (d. Eugène Lourié USA 1953)

Them! (d. Gordon Douglas USA 1954)

Internet

Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/godzilla/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknwon. ‘Godzilla 1998’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/godzilla-1998 (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla 2014’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/godzilla_2014/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘Godzilla 2014’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/godzilla-2014 (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknown, ‘Kaiju’ on pixiv.net at http://dic.pixiv.net/a/%E6%80%AA%E7%8D%A3 (last accessed using an online translator 25/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘King Kong (1933)’ on the-numbers.com at http://www.the-numbers.com/movie/King-Kong-(1933)#tab=summary (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘King Kong (1933)’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1011615_king_kong (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘Pacific Rim (2013)’ on rottentomatoes.com at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/pacific_rim_2013/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknown. ‘Pacific Rim’ on metacritic.com at http://www.metacritic.com/movie/pacific-rim (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Author Unknown, ‘The 50s B-Movie’ on glyndwr.ac.uk at https://www.glyndwr.ac.uk/rdover/other/the_50s_.htm (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Birch, Nathan. ‘5 Reasons ‘Pacific Rim’ Failed as a Kaiju Movie’ on uproxx.com at http://uproxx.com/gammasquad/5-reasons-pacific-rim-fails-as-a-kaiju-movie/2/ (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Gates, Anthony. ‘Godzilla vs Hedorah aka Godzilla vs the Smog Monster’ on easternkicks.com at http://www.easternkicks.com/reviews/godzilla-vs-hedorah-aka-smog-monster (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Harvey, Ryan. ‘A History of Godzilla Part 1: Origins (1954-1962)’ on blackgate.com at https://www.blackgate.com/2013/12/16/a-history-of-godzilla-on-film-part-1-origins-1954-1962/ (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Harvey, Ryan. ‘A History of Godzilla Part 2: The Golden Age (1963-1968)’ on blackgate.com at https://www.blackgate.com/2014/01/07/a-history-of-godzilla-on-film-part-2-the-golden-age-1963-1968/ (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Harvey, Ryan. ‘A History of Godzilla Part 4: The Heisei Era (1984-1996)’ on blackgate.com https://www.blackgate.com/2014/02/18/a-history-of-godzilla-on-film-part-4-the-heisei-era-1984-1996/ at (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Harvey, Ryan. ‘A History of Godzilla Part 5: Travesty and the Millennium Era (1996-2004)’ on blackgate.com https://www.blackgate.com/2014/05/12/a-history-of-godzilla-on-film-part-5-the-travesty-and-the-millennium-era-1996-2004/ at (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Knipfel, Jim. ‘Godzilla 1998: What went wrong with the Roland Emmerich film?’ on denofgeek.com at http://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/godzilla/233267/godzilla-1998-what-went-wrong-with-the-roland-emmerich-film (last accessed 27/03/2017)

‘The lone Kaiju’ ‘Kaiju’ on urbandictionary.com at http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=kaiju (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Sargent, J. F. ‘How ‘Pacific Rim’ Got Kaiju Wrong’ on filmschoolrejects.com at https://filmschoolrejects.com/how-pacific-rim-got-kaiju-wrong-c154c1499531 (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Sell, Paul. ‘The History of King Kong: A Prelude to Kong: Skull Island’ on tohokingdom.com http://www.tohokingdom.com/articles/2016-08-17_history_king_kong_prelude_skull_island.html (at last accessed 28/03/2017)

Suvarna, Vivek. ‘Gojira: The Japanese Original’ on thefocuspull.com at http://www.thefocuspull.com/features/gojira-japanese-original/ (last accessed 25/03/2017)

Wilson, Karina. ‘1950s’ on horrorfilmhistory.com at http://www.horrorfilmhistory.com/index.php?pageID=1950sa (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Vary, Adam B. ‘‘Godzilla’:’I know I screwed up,’ says Dean Devlin’ on ew.com at http://ew.com/article/2012/07/27/dean-devlin-on-godzilla-reboot/ (last accessed 27/03/2017)

‘Venoms5’ ‘Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (1995) Review’ on coolasscinema.com http://www.coolasscinema.com/2014/05/gamera-guardian-of-universe-1995-review.html at (last accessed 28/03/2017)

Magazines

Robert Biondi, “The Evolution of Godzilla – G-Suit Variations Throughout the Monster King’s Twenty One Films”, G-FAN #16 (July/August 1995)

Vlog

Cinemasins episode ‘Everything wrong with Godzilla in 7 minutes or less’ at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oF4RxoBzTpo (last accessed 27/03/2017)

Leave a Reply